As a psychologist who provides services for older adults, I’ve noticed that, though my older clients have a variety of reasons for seeking help, their underlying issues often coalesce around common themes. Specifically, those deeper issues often entail concerns over what they’ve done with their lives.

Here are a few reasons that clients have come for help, along with underlying issues that then emerged in the course of therapy (some details have been changed to protect confidentiality):

- A woman in her late 70s sought help for depression evoked by a highly critical husband. An underlying issue was her disgust with herself for having spent over 40 years with someone who consistently tore her down.

- A woman in her early 70s sought help for anxiety related to finances. She and her husband had built a successful business, but, after her husband’s death 15 years earlier, a son had mismanaged the business, and it failed. An underlying issue was whether it had made sense to spend her life building something that didn’t last.

- A man in his mid 60s sought help for suicidal thoughts that occurred after years of being berated by a bullying boss. An underlying issue was dissatisfaction with having spent his whole life trying to please others who mistreated him, beginning with his irate, drunken father.

- A man in his late 50s sought help for obsessions and compulsions centered on cleanliness and order. An underlying issue was that he had always wanted a lifelong, intimate relationship, but his desire for control over his surroundings had driven away prospective mates.

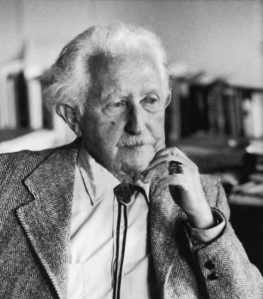

Though these people had each been coping for years with the problem they first described to me, what had changed for each of them was that they had become increasingly dissatisfied with how they had lived their lives. This in turn led all of them to be critical of themselves for not having lived differently. A psychological perspective that helps explain what had happened in each case is psychoanalyst Erik Erikson’s theory of psychosocial development. He proposed that a person’s sense of self and of his or her relationship to the social world develops through a series of eight stages. In each stage, events challenge the self in some way. There is a resulting conflict between developing some psychological characteristic (for example, a sense of trust) or failing to develop that characteristic (e.g., being mistrustful). In the last of these stages, occurring in late adulthood, the conflict is between ego integrity and despair. The person reflects back on the life he or she has lived and comes away either satisfied or dissatisfied with that life. If one feels content with decisions made and proud of accomplishments, there is a sense of integrity and wholeness. On the other hand, if one regrets what he or she has done or failed to do, there is emptiness and despair. Each of the clients mentioned above had some degree of this despair.

What’s to be done with the despair of late adulthood? No matter how much we may wish to, none of us can go back and take the road we passed by long ago. Dwelling on what might have been only intensifies the misery. Often, a change in perspective is needed. Here are some thoughts I’ve found could be helpful for those experiencing regret late in life:

- Be aware that the best choice may seem clear now, but probably wasn’t clear at the time. It may be a cliché to say that hindsight is 20-20, but it is true. At one point, that marriage or business or career seemed rife with promise, and there probably was much to recommend it. Conversely, there may have been good reasons for avoiding what now seems to have been the better option.

- Explore the positives that occurred as a result of the path chosen. Who benefited? What good thing wouldn’t have occurred had you chosen differently? The woman whose business failed was consoled when she realized that the business had both allowed her time to build a close relationship with her children and provided ample income for their educations.

- Remember that each day provides a new opportunity to make more satisfying choices. I can’t do anything about having cowered before a bullying boss in years past, but I can learn how not to cower today, and perhaps can find a way to change or leave that and other destructive relationships.

- Each day also is an opportunity to take care of myself rather than to berate myself. Rather than living in the past, I can put emphasis on what provides joy and comfort in the present—good friends, grandchildren, digging in the garden, reading a good book, a cup of soup on a cold day, a glass of lemonade on a hot one.

- Think of how you would act toward someone else who made choices similar to yours. If you wouldn’t condemn them, it doesn’t make sense to condemn yourself. Be as compassionate toward yourself as you would be toward others.

- Some bad outcomes or missed opportunities need to be grieved. Name the sadness and let yourself feel it. Recognize the loss as loss, but DON’T ruminate on what could have been done differently. Dwelling on what you think you should have done can keep you from completing the grieving process.

- Focus not on ego but on spirit. Despair is a reaction of the ego to perceived inadequacies. “ I made bad decisions, I should have known better.” Life is about much more than building up one’s ego, though. We are spirit, and that spirit thrives when we surrender our ego to God, whose majesty dwarfs both our successes and our failures. Surrendering our ego to Him, we can recognize that He often brought good even out of our most wretched decisions. Even more, we recognize that we are enfolded in His love; from the shelter of His arms, neither accomplishments nor failings loom as large as they do from the perspective of our egos.

If you’re experiencing regret over how you’ve lived your life, consider how these points might apply to you. Often, facing regrets is the first step to making peace with them.