I’ve written some about the changes that have taken place for me since deciding that I was not just old but ‘old-old’, at a point where I am not likely to have many more years of health and vitality. My awareness of that seems to be associated with entering different stage of life, a realization that prompts me to review what others have written about life stages.

In the mid-twentieth century, psychoanalyst Eric Erikson theorized that the final stage of psychosocial development consisted of reviewing one’s life and either finding meaning and satisfaction in one’s accomplishments or, conversely, seeing mostly failures and missed opportunities. The person thus goes through a process leading to either integrity or despair. This is the most popular theory of late-life psychosocial development, but not the only one. Ten years ago, I described in this blog the views of Lewis Joseph Sherrill, contemporaneous with Erikson but with an educational and theological background, rather than a psychoanalytic one. He thought that the final stage of adulthood consisted of simplification. He described this as “distinguishing the more important from the less important, getting rid of the less important or relegating it to the margin; and elevating the more important to the focus of feeling, thought, and action.” I wrote a series of posts on simplification in late life.

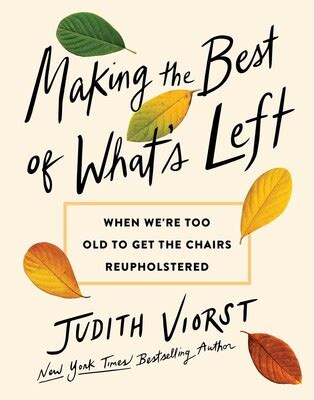

I thought about these ideas recently while reading Judith Viorst’s Making the Best of What’s Left: When We’re too Old to Get the Chairs Reupholstered, an alternately lighthearted and somber account of life past age 90. She describes Erikson’s theory, then notes that he was talking about people in their mid-60s. She asks, “how long can people look back on their accomplishments?” She suggests there must be another stage beyond what Erikson describes.

I’m 17 years younger than Viorst, but the changes that have taken place in me over the past year or so make me think there is something to her suggestion. I did quite a bit of life review during the roughly ten years after I retired from full-time work. I’m not thinking as much as I did then about what I accomplished and where I fell short. (There’s one area that’s an exception to that, which I may write about at some point.)

As for simplification, I see my life as simpler than it was in some of the areas that Sherill talked about–especially status, character, and the material realm. I suspect that making life simpler is a project that will continue until I die, but I’m not currently devoting much effort to the process. Here, too, the supposed last stage of development seems to have come and gone. So what comes next?

I haven’t identified a key issue for this phase of life, but I have noticed a few changes in my usual state of mind that may be associated with some sort of transition. First, I notice more happy bemusement, second, I have a sense of constrained freedom.

First, the happy bemusement. Imagine having an old car that you’ve driven more miles than you expected. You tell yourself that this can’t last forever, that the engine or transmission or something else major will go bad, and that will be the end. Nevertheless, it keeps on puttering along, the numbers on the odometer climbing higher and higher. You’re surprised, and also glad, and eventually entertained by its durability. The older I get, the more I’m struck by how well my body continues to function when so many others are having significant, sometimes life-threatening problems. I’m glad to be doing so well. Sometimes I think that this can’t last and I should be prepared for cancer, heart disease, or something else major to strike. Mostly, though, I am grateful. I shake my head in wonderment.

How about constrained freedom? When I wrote about my relationship to time, I noted that, until recently, there was always something I had to do–work, raise children, care for parents, etc. Now, there’s nothing I have to do. There’s considerable freedom in that. Freedom is of course double-edged, both welcome but in some ways burdensome. If I can do anything, what will I do? How will I decide?

My freedom isn’t total, though, but a constrained freedom. The constraint is age. I may not have many years left, or, if I do, illness or disability may intrude. So it would be unwise for me to embark on a project that would take ten or twenty years to come to fruition; I wouldn’t be likely to complete it.

Freedom plus limited time pushes me to live in the present much more than I ever have. Through much of life, thinking about and investing for the future was the sensible thing to do. Aesop warned us: Be like the ant, not the grasshopper! The ant prepares for winter, but how will he act once winter arrives? Once there’s no more need to strive and save, can he relax and enjoy himself? That’s the question I’m faced with. I don’t need to work or plan anymore. Can I live happily in that freedom?

So maybe those are the challenges of being old-old while still healthy and reasonably vigorous: To be grateful rather than worried about eventual decline, and to live well within this recently arrived-at, genuine, but also limited freedom. At present, I’m using this freedom for something I hadn’t planned on: Over the last year, I’ve been dating a wonderful woman, and we plan to be married. I plan to write about that relationship and how it fits into this stage of life in a future post.